TL;DR

This newsletter is about why organisations should care about data rights and how to comply with them in practice. It looks at the value of data rights compliance, how this can be done in a more integrated manner and what this looks like in the context of AI governance.

Here are the key takeaways:

Data rights compliance is sometimes viewed as an annoying inconvenience that stifles innovation and progress. Those in the data rights space involved in the shaping, applying or enforcing of data rights may therefore be perceived as perpetuators of stagnation.

There is some evidence of this happening in Europe. Mario Draghi's report shows how the EU's complex web of regulations may be partly responsible for the lagging growth in the region as well as the lack of a thriving tech sector.

However, rather than stifling innovation and growth, data rights professionals can help organisations to better position themselves to improve their products or services or how they do things. This includes taking advantage of the opportunities presented by the latest AI wave.

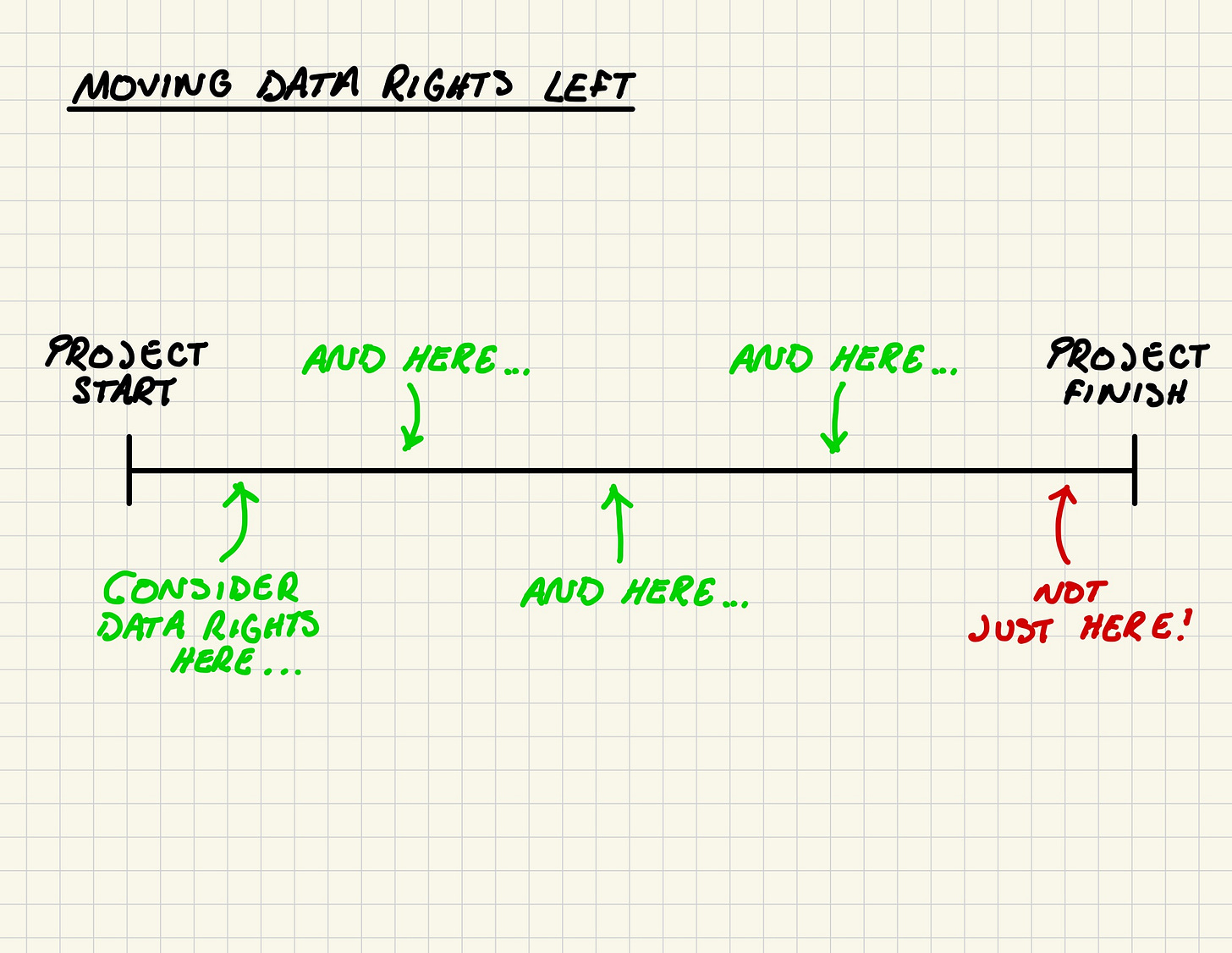

To do this, organisations need to focus on moving data rights left. This means considering data rights compliance issues in a more integrated and efficient fashion so that they are not addressed at the last moment and become a bottleneck.

By moving data rights left, organisations can achieve three things:

Be in a position to take advantage of new technologies

Avoid data rights disasters

Gain a valuable USP

Moving data rights left in the context of AI development and adoption requires data rights professionals to be proactive in their compliance work and collaborate with different stakeholders. This is to ensure that there is a balance between the business goals of the organisation and data rights.

In the context of AI governance, moving data rights left means addressing three key questions:

What is the AI landscape/how are companies currently using AI?

What are the problems/pain points of this journey?

How do we solve these problems/ease the pain (balancing data rights with business goals)?

Intro

In What data rights are for, I put forward a concise case for why I think data rights in this modern digital age are so important and therefore why people should exercise them when they can.

What data rights are for (#2) expanded on these ideas by looking at the surveillance capitalist model and the negative externalities that data rights are designed to protect you from.

With these previous posts, I explored why data rights are important from the perspective of the users of powerful digital systems. But with this post, I take a slightly different approach by looking at why data rights are important for the builders of powerful digital systems.

In other words, in this post I attempt to answer the following question:

To what extent should builders of powerful digital systems be concerned with data rights, and what does this look like in practice?

Ultimately, data rights law is about protecting individuals. But to achieve this, organisations building and operating powerful digital systems need to implement various measures to ensure compliance with the law and in turn respect people's rights. These measures (whether they are legal, organisational or technical in nature) are designed to tackle some of the harms and risks that arise from the deployment or use of powerful digital systems. However, such compliance work is sometimes viewed as an annoying inconvenience or even a means of stagnation.

I briefly make reference to this in What data rights are for (#2) in the context of the surveillance capitalist model and the nature of such a system:

Data rights provide a means for confronting the surveillance capitalist machine.

But in the first place, as an individual, if you can help it, do not feed the machine!

Do not give your data to entities that are not incentivised to use it in your best interests. Do not give your data to those who are not incentivised to use it ethically or fairly.

Do not give your data to those who will not look after it.

If you understand the system at play, which is set out in this post, then you will understand why:

[...]

A system that is represented by mantras like 'move fast and break things' whereby the supposed beneficial ends always, somehow, justify the means and anyone who argues otherwise are simply luddites determined to stifle progress and growth. (Emphasis added)

I used 'luddites' ironically to essentially refer to those in the data rights space. This includes the legal/compliance/policy experts, practitioners, auditors, regulators and any others involved in the shaping, applying or enforcing of data rights.

(I say ironically because I too am in the data rights space.)

But are these various people and entities in the data rights space actually luddites? Some definitely seem to think so.

One such person is Marc Andreessen, co-founder and general partner of the prominent Silicon Valley venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz. In his Techno Optimist Manifesto, Andreessen describes how technological development is essential for progress and improving the human condition:

Lies

We are being lied to.

We are told that technology takes our jobs, reduces our wages, increases inequality, threatens our health, ruins the environment, degrades our society, corrupts our children, impairs our humanity, threatens our future, and is ever on the verge of ruining everything.

We are told to be angry, bitter, and resentful about technology.

We are told to be pessimistic.

The myth of Prometheus – in various updated forms like Frankenstein, Oppenheimer, and Terminator – haunts our nightmares.

We are told to denounce our birthright – our intelligence, our control over nature, our ability to build a better world.

We are told to be miserable about the future.

Truth

Our civilization was built on technology.

Our civilization is built on technology.

Technology is the glory of human ambition and achievement, the spearhead of progress, and the realization of our potential.

For hundreds of years, we properly glorified this – until recently.

I am here to bring the good news.

We can advance to a far superior way of living, and of being.

We have the tools, the systems, the ideas.

We have the will.

It is time, once again, to raise the technology flag.

It is time to be Techno-Optimists.

Notice how Andreessen frames concerns about technology taking our jobs, reducing wages, increasing inequality, threatening health, ruining the environment, degrading our society, corrupting children, impairing our humanity, threatening the future and being on the verge of ruining everything as part of "the lie". This means that advocates of these concerns are opposing ‘the truth’, which is that technological development has been the key to the success of civilization and ‘the glory of human ambition and achievement’.

So who would be the advocates of "the lie"? Perhaps it would be ‘techno-pessimists’, the ones who raise concerns about data protection, online safety, influence operations, surveillance capitalism, algorithmic bias and the other various risks of modern technology. In fact, in his manifesto, Andreessen explicitly calls out such people:

The Enemy

We have enemies.

Our enemies are not bad people – but rather bad ideas.

Our present society has been subjected to a mass demoralization campaign for six decades – against technology and against life – under varying names like “existential risk”, “sustainability”, “ESG”, “Sustainable Development Goals”, “social responsibility”, “stakeholder capitalism”, “Precautionary Principle”, “trust and safety”, “tech ethics”, “risk management”, “de-growth”, “the limits of growth”.

This demoralization campaign is based on bad ideas of the past – zombie ideas, many derived from Communism, disastrous then and now – that have refused to die.

Our enemy is stagnation.

Our enemy is anti-merit, anti-ambition, anti-striving, anti-achievement, anti-greatness.

Our enemy is statism, authoritarianism, collectivism, central planning, socialism.

Our enemy is bureaucracy, vetocracy, gerontocracy, blind deference to tradition.

Our enemy is corruption, regulatory capture, monopolies, cartels.

Our enemy is institutions that in their youth were vital and energetic and truth-seeking, but are now compromised and corroded and collapsing – blocking progress in increasingly desperate bids for continued relevance, frantically trying to justify their ongoing funding despite spiraling dysfunction and escalating ineptness.

Our enemy is the ivory tower, the know-it-all credentialed expert worldview, indulging in abstract theories, luxury beliefs, social engineering, disconnected from the real world, delusional, unelected, and unaccountable – playing God with everyone else’s lives, with total insulation from the consequences.

[…]

Our enemy is the Precautionary Principle, which would have prevented virtually all progress since man first harnessed fire. The Precautionary Principle was invented to prevent the large-scale deployment of civilian nuclear power, perhaps the most catastrophic mistake in Western society in my lifetime. The Precautionary Principle continues to inflict enormous unnecessary suffering on our world today. It is deeply immoral, and we must jettison it with extreme prejudice.

[…]

We will explain to people captured by these zombie ideas that their fears are unwarranted and the future is bright.

We believe these captured people are suffering from ressentiment – a witches’ brew of resentment, bitterness, and rage that is causing them to hold mistaken values, values that are damaging to both themselves and the people they care about.

We believe we must help them find their way out of their self-imposed labyrinth of pain.

We invite everyone to join us in Techno-Optimism.

With this worldview, Andreessen is attempting to illustrate a contrast between the so-called builders and so-called luddites.

The builders are concerned with building the future and improving the human condition. Luddites are more concerned with the risks of such activity.

However, according to Andreessen, the missions of both groups are fundamentally contradictory. There is no way to develop technology that progresses society if we are constantly critiquing such technology and placing limits on its very development based on its various risks.

Andreessen is very clearly against those placing such limits on technology. In his piece called Why AI Will Save the World, he characterises the luddites as Baptists, namely those who "legitimately feel – deeply and emotionally, if not rationally – that new restrictions, regulations, and laws are required to prevent societal disaster" (drawing parallels with the advocates of the prohibition of alcohol in the US during the 1920s). These Baptist, or 'doomers', include "AI safety experts", "AI ethicists", "AI risk researchers" and essentially all those in the data rights space. These people believe more in the risks of AI than the benefits of AI.

And if they believe more in the risks than the benefits of AI, then the precautionary principle suggests that more limits and controls must be placed on such a technology.

For Andreessen, given his strong belief in AI providing a way to "make everything we care about better", placing limits or controls on its development is akin to being anti-progress. It is akin to being a luddite.

In some ways, Andreessen could be right. But I ultimately believe that he cannot be right.

In fact, if data rights are implemented correctly, there is a way to balance the missions of the so-called builders and the so-called luddites. There is a way to help build machines of loving grace.

Why Andreessen could be right

It is important to clarify what data rights professionals like myself actually do.

We basically help solve legal/policy problems within an existing legal/policy framework.

Laws are the rules that govern our society in various ways. They dictate what we can and cannot do, and stipulate our rights and responsibilities.

However, these rules cover the many events, transactions and activities that feature in our societies. It makes understanding and following all these rules very difficult for the average person.

This is what makes the law a barrier for people as they try navigate their way through society. They struggle to find the laws that apply to their particular situations and the actions they are permitted to take based on those applicable laws.

These are the legal problems that data rights professionals solve. They provide solutions to these problems by helping to figure out three things:

The objective that the client wants to pursue

The laws that apply to the pursuance of this objective

The actions that can be taken by the client as permitted by the applicable laws

But herein lies the potential problem with data rights professionals that Andreessen hints at; they are essentially trained to be risk-averse pessimists by default.

When data rights professionals are developing their legal solutions, they are trying to eliminate or mitigate risks for the client. They are trying to ensure that the client does not fall on the wrong side of the law whilst achieving what they want to achieve.

But this means that data rights professionals are predominantly looking for how things can go wrong. And it is this kind of mindset that Andreessen is referring to in his depiction of "the enemy."

This includes his criticism of the 'precautionary principle', a concept codified in EU law:

The precautionary principle is an approach to risk management, where, if it is possible that a given policy or action might cause harm to the public or the environment and if there is still no scientific agreement on the issue, the policy or action in question should not be carried out. However, the policy or action may be reviewed when more scientific information becomes available. The principle is set out in Article 191 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

The problem that people like Andreessen have with the precautionary principle and the mindset it embodies is that it promotes a crippling form of risk intolerance upheld by the "tyranny of bureaucratization."1 Such bureaucratization is evident across various different social domains, partly manifested in a massive bloating of legal codes and regulation.

Andreessen and other like-minded people view all of this as part of an ideology of stasis that stifles innovation and progress in society:

...bureaucratic norms, organizations, and languages have become institutionalized, transferring more power to a managerial elite. This constant bureaucratization is paralleled by the desire for total quantification across government, business, and academia, wherein progress depends on meeting predefined metrics. Granted, risk management, which often requires quantification, has been critical for civilization's progress; some have even claimed that advances in probability theory, which helps control risk, ignited the scientific and industrial revolutions that separated the preindustrial era from modernity. But while quantification has contributed to increased managerial efficiency and scientific progress, our current desire to measure and control all risk has reduced our collective willingness to take any. Instead of mastering uncertainty and embracing ambiguity, we quantify risk in hopes of eliminating it. This zero-risk bias not only impedes innovation, it can backfire.2

A culture based on risk avoidance and intolerance is one that prefers the status quo over change. This inevitably makes great advances and innovation much more difficult, since such efforts are inherently risky and threaten the status quo. Less volatility may mean more stasis, but there is also less chance of improving things if they more-or-less stay the same.

Where does such a culture exist? One might point to the EU. Or you could even say the EU has pointed to itself.

Back in September 2024, Mario Draghi, former prime minister of Italy and president of the European Central Bank, released his report on European competitiveness. Below is an extract from the Foreword:

Europe has been worrying about slowing growth since the start of this century. Various strategies to raise growth rates have come and gone, but the trend has remained unchanged.

Across different metrics, a wide gap in GDP has opened up between the EU and the US, driven mainly by a more pronounced slowdown in productivity growth in Europe. Europe’s households have paid the price in foregone living standards. On a per capita basis, real disposable income has grown almost twice as much in the US as in the EU since 2000.

[...]

Technological change is accelerating rapidly. Europe largely missed out on the digital revolution led by the internet and the productivity gains it brought: in fact, the productivity gap between the EU and the US is largely explained by the tech sector. The EU is weak in the emerging technologies that will drive future growth. Only four of the world’s top 50 tech companies are European.

[...]

This is an existential challenge.

The only way to meet this challenge is to grow and become more productive, preserving our values of equity and social inclusion. And the only way to become more productive is for Europe to radically change.3

But how has Europe managed to find itself confronted with this existential challenge? It could be at least partly to do with its vast and complex regulatory framework. Further on in the report it states:

Europe is stuck in a static industrial structure with few new companies rising up to disrupt existing industries or develop new growth engines. In fact, there is no EU company with a market capitalisation over EUR 100 billion that has been set up from scratch in the last fifty years, while all six US companies with a valuation above EUR 1 trillion have been created in this period. This lack of dynamism is self-fulfilling.

The problem is not that Europe lacks ideas or ambition. We have many talented researchers and entrepreneurs filing patents. But innovation is blocked at the next stage: we are failing to translate innovation into commercialisation, and innovative companies that want to scale up in Europe are hindered at every stage by inconsistent and restrictive regulations. (Emphasis added)4

In the area of tech law and policy, the EU has passed/brought into force plenty of legislation in recent years. The GDPR came into force in 2018, the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act were passed in 2022, and the AI Act was passed in 2023. That is a lot of hefty and impactful regulation coming into existence over a 5-year period. The Draghi report suggests that such legislation forms as regulatory barriers that are particularly onerous on young companies in the tech sector.5

And the EU prides itself as a 'world leader' in terms of regulation. Dubbed the 'Brussels effect', the EU is known for the extra-territorialisation of its laws that ends up influencing standards in other jurisdictions. When the EU passed the AI Act in late 2023, there was this tweet from the then Internal Markets Commissioner in the European Commission Thierry Breton:

It seems clear from the likes of Draghi and Breton that the EU is more focused on regulating AI than building it. As a consequence, Europe has experienced slow growth, a slacking tech sector relative to the US and very little innovation coming from the continent. Europe has suffered from an ideology of stasis.

For Andreessen et al, those in the data rights space perpetuate this ideology and its constituent problems. With a complex web of regulations in place, data rights professionals guide others on the actions they can and cannot take in pursuing their respective objectives. But in doing so, they perform their role as risk-averse pessimists who impose the various restrictions dictated by the bureaucracies above. 'No you cannot do x because provision y of law z says you cannot do x.' 'Before you do x you need to consult y stakeholders and carry out z impact assessment before doing x.' 'If you do x you will be exploiting a legal grey area and you are at a high risk of being sanctioned by regulators or being sued.' Party poopers, naysayers, killjoys, cynics. Data rights professionals are luddites.

Why Andreessen cannot be right

Abeba Birhane's thesis, Automating Ambiguity: Challenges and Pitfalls of Artificial Intelligence, (which I have written about previously) is a brilliant antithesis of the current hype that exists around AI. But while her work contains heavy critiques of AI and the industry behind it, Birhane does admit this at the end:

This thesis is first and foremost an endeavour to critically examine both the scientific basis and ethical dimensions of current ML/AI. Thus, it primarily lays bare the limitations, failings, and problems surrounding AI systems broadly construed. But this is not to imply that AI systems cannot be beneficial (to marginalized communities, AI is already beneficial to the wealthy and powerful), or cannot function in a way that serves the most disenfranchised or minoritized. Far from it. It is possible and important to envision such a future. (Emphasis added)6

Technological development does encompass benefits and risks. This is especially when the development is driven by corporations with their motives and incentives (see What data rights are for #2).

We therefore need data rights professionals. We need them in order to minimise the risks and maximise the benefits. We get criticised for focusing too much on the former and not enough of the latter. This is why we are seen as risk-averse pessimists.

But data rights professionals can be more than this.

Data rights professionals cannot just be part of a managerial class merely concerned with "the organization and allocation of productive activity as opposed to the production of anything in particular." They cannot just be a conveyer belt for "orders flowing in from above."

Compliance with data rights provide a way for organisations to better position themselves to improve their products or services or how they do things.

Look at the current AI wave. More and more companies are using open models to either improve internal processes or to build/augment their products or services. Whilst there remains a lot of hype around exactly how capable these models are and what they can therefore be used for, lots of companies are experimenting or at least thinking about how to use them. But for any company to be able to take full advantage of these open models, there is no escaping the fundamental first-order issue of data rights.

Let's say a European retail company wants to fine-tune an open LLM to build a customer service chatbot. To do this, the company will need large datasets of conversational text, customer queries and customer responses. To pursue such a project, the company will need to know what they can use to make this chatbot a reality. It will need to know about its data lifecycle (including the data they collect, what its used for, where its stored, who it is shared with etc). This knowledge is not just needed for legal compliance purposes, such as identifying an appropriate legal basis under the GDPR to use the data for building a chatbot (to the extent that the dataset contains personal data). This type of knowledge is crucial for knowing whether building such a product is even feasible in the first place.

This is the value that data rights professionals can provide. They can help with the work required to get an organisations' data rights in order. They can help organisations better understand what data they hold, how it is used and what they can use it for. So if a company wanted to build a customer chatbot, data rights professionals could be relied on to provide the crucial guidance on the feasibility of such an endeavour, both from a compliance and a business perspective. They can help ensure that the right infrastructure and measures are in place to take advantage of open AI models.

Essentially, data rights professionals help companies avoid looking like this:

The complex web of regulations that exist may indeed be complicated, but they are not completely unnavigable. You can think of legal frameworks like the rules of chess and the chess board. It is true that the rules and the board restrict the moves that one can make with the different pieces. However, even within these restrictions, there are many moves that can nevertheless be made and therefore many different strategies that can be used to ensure success. The job of data rights professionals is to study this chessboard and help come up with the right moves to win. Their job is to figure out the objective, identify the applicable law, and provide a set of actions to achieve the objective that also complies with the applicable law.

But in order to do this the right way, you need to move data rights left.

What is moving data rights left?

This meme does a good job at capturing how data rights professionals and legal teams are sometimes used or consulted:

Legal/compliance teams are sometimes consulted at the last moment. And then when legal/compliance look at the project and say 'sorry but you can't do this because of x, y and z law', they are seen as unreasonable bottlenecks.

But this is all wrong.

Moving data rights left means considering data rights in a more integrated and efficient fashion:

It is about considering data rights implications at the earliest possible moment of a project and shaping it accordingly. By doing this, you can navigate through the chessboard in a more effective way and avoid legal becoming bottlenecks and basically killing projects.

If you want to ride the latest AI wave, you need to move data rights left.

Why move data rights left?

Moving data rights left allows organisations to achieve three things:

Be in a position to take advantage of new technologies. For any AI project, having the right data and knowing how to use it is key. Data rights compliance helps organisations with this work as it requires organisations to have a good understanding of what data they hold and how it is used. Such compliance will in turn help implement the necessary processes, policies and procedures in place that will be essential for any AI project, including leveraging open models. Moving data rights left means doing this work earlier, and the earlier this is done the easier AI adoption becomes.

Avoid data rights disasters. I mentioned several data rights disasters in What data rights are for (#2) in relation to the development of Facebook. For example, with the news feed, the customer support team warned about the perceived invasion of privacy that the feature would invoke, but these concerns were just "brushed off" and seen as a "distraction" by Zuckerberg and others who went ahead with the launch regardless. Luckily for Facebook, the backlash it received after ignoring these warnings did not bring it down, as was the case with the introduction of its targeted advertising features and the Like button. But this may not always be the case for companies taking risks with data rights. Carey Leningprovides some great coverage of various privacy disasters at companies that are more existentially threatening, such as the rather unbelievable (and slightly comical) story of Calmera. Moving data rights left means spotting the glaring issues earlier, and providing time to fix them before it is too late.

Gain a valuable USP. Many will not see the value creation that data rights compliance brings. But doing this compliance in a more integrated fashion rather than as a late add-on not only ensures being on the right side of the law, but also signals to others that you take data rights seriously. Whether B2B or B2C, this can be an incredibly valuable USP or competitive advantage, especially in the midst of a sprawling regulatory framework where achieving effective compliance can be difficult.

How do you move data rights left?

Moving data rights left requires data rights professionals to be collaborative enablers.

They need to be capable of working with various different teams. This requires professionals in the form of expert generalists (or T-shaped individuals); they ought to have a deep knowledge in at least one area combined with a good level of knowledge spread across a number of neighbouring areas. Such a skillset is what can enable data rights professionals to communicate legal and policy requirements to various stakeholders within an organisation and work towards practical solutions to achieve compliance.

This is the way to balance data rights with business goals, and will therefore be crucial for effective AI governance. And with more AI-related laws and policies being developed across the world, the need for effective governance will also increase. If this is done the right way by moving data rights left, and organisations can ride the AI wave whilst remaining compliant.

In the context of AI governance, moving data rights left means addressing three key questions:

What is the AI landscape/how are companies currently using AI?

What are the problems/pain points of this journey?

How do we solve these problems/ease the pain (balancing data rights with business goals)?