The most important thing for AI in 2026

What is overlooked when building modern machines

Most people will be focusing on the wrong things when it comes to AI in 2026.

Most people will be focusing on the emerging paradigms, the new breakthroughs, or the next groundbreaking model claimed to be AGI.

They are wrong.

What is far more important is something that too often gets overlooked. Something that is lethally ignored until it is too late. Something that, if done well, unlocks the real power of AI in a way that is not only sustainable but beats 99% of the competition.

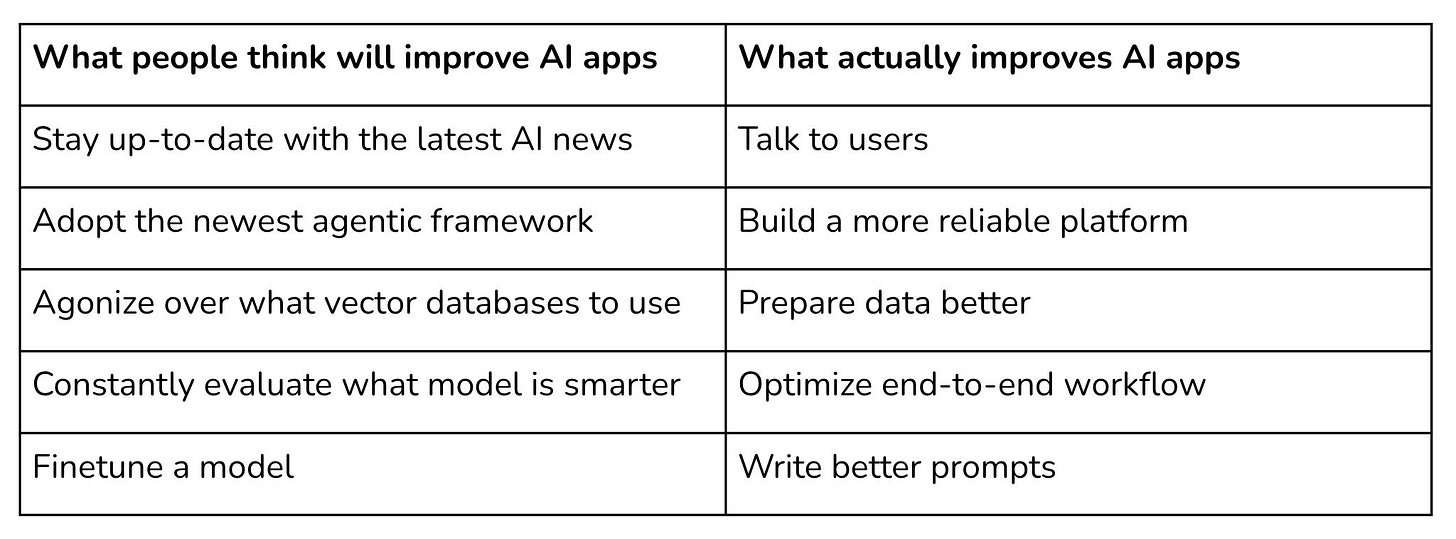

To build good AI products, it is a mistake to obsess over the latest and greatest models. Chip Huyen, an experienced computer scientist and author of AI Engineering: Building Applications with Foundation Models, makes this point exactly. For her, the things that actually contribute to better AI products are talking to users, building a more reliable platform, using better data, optimising for end-to-end workflows and writing better prompts.

If you want customers to invest in your product, they need to be a position to trust your product. When the hype and bravado eventually fade away, trust is the currency that keeps customers around.

What all this means is that the most important thing for AI developers to focus on in 2026 and beyond is governance.

This is not because it is required by law. Or because it is a ‘nice-to-have’. Or even because it is good for PR.

Governance is a business-enabler. It is a way of deepening moats. It is the dynamic equilibrium that balances innovation and order.

Good governance is what underpins good, reliable AI products that actually work, build trust and deliver value.

As my last newsletter for 2025, I want to look to 2026 and what I think is next for AI from a data rights and governance perspective. I want to share what I think the AI landscape will probably look like, the problems it will produce, and why governance is the way to solve them.

The AI landscape in 2026

AI capabilities may slow down and continue to be jagged.

AI is proving capable at completing an increasing number of tasks, including those thought to be exclusively reserved for humans. Some expect this trend to continue into the future.

But this might not necessarily be the case.

The current improvement in capabilities have relied heavily on scaling laws - an empirical observation that model capabilities increase as the size of the model, the amount of training data and amount of compute used for training increases. There is also the possibility of a scaling law related to test-time compute, whereby increasing the amount of time (and therefore computing power) a model spends ‘thinking’ of an answer to an input also increases performance.

Continuing to scale these various aspects of AI development and deployment cannot go on forever for the simple reason that the resources required for this are scarce. There is only so much data you can collect for training and there is only so much GPU-powered data centres that you can build.

This is an argument that Ilya Sutskever, co-founder and former chief scientist of OpenAI, has been making for a while now. During a talk Sutskever gave at NeurIPS 2024 in Canada, he stated that “pre-training as we know it will eventually end.”

More recently on the Dwarkesh Podcast, Sutskever said this:

At some point...pre-training will run out of data. The data is very clearly finite. What do you do next? Either you do some kind of souped-up pre-training, a different recipe from the one you’ve done before, or you’re doing RL, or maybe something else. But now that compute is big, compute is now very big, in some sense we are back to the age of research.

The scarcity of resources means that scaling cannot continue to be (at least predominantly) relied on for model improvement. Scaling laws are attractive because they provide a predictable, and therefore low-risk, means for improving AI models; you essentially just need to invest more in compute and data. But as Sutskever suggests, scaling has its limits, and if we are reaching those limits, then something different may be required for the next great leaps in AI models.

The gains from transformers for reasoning, planning and alignment may soon be exhausted.

Accordingly, AI model capabilities may start to slow down.

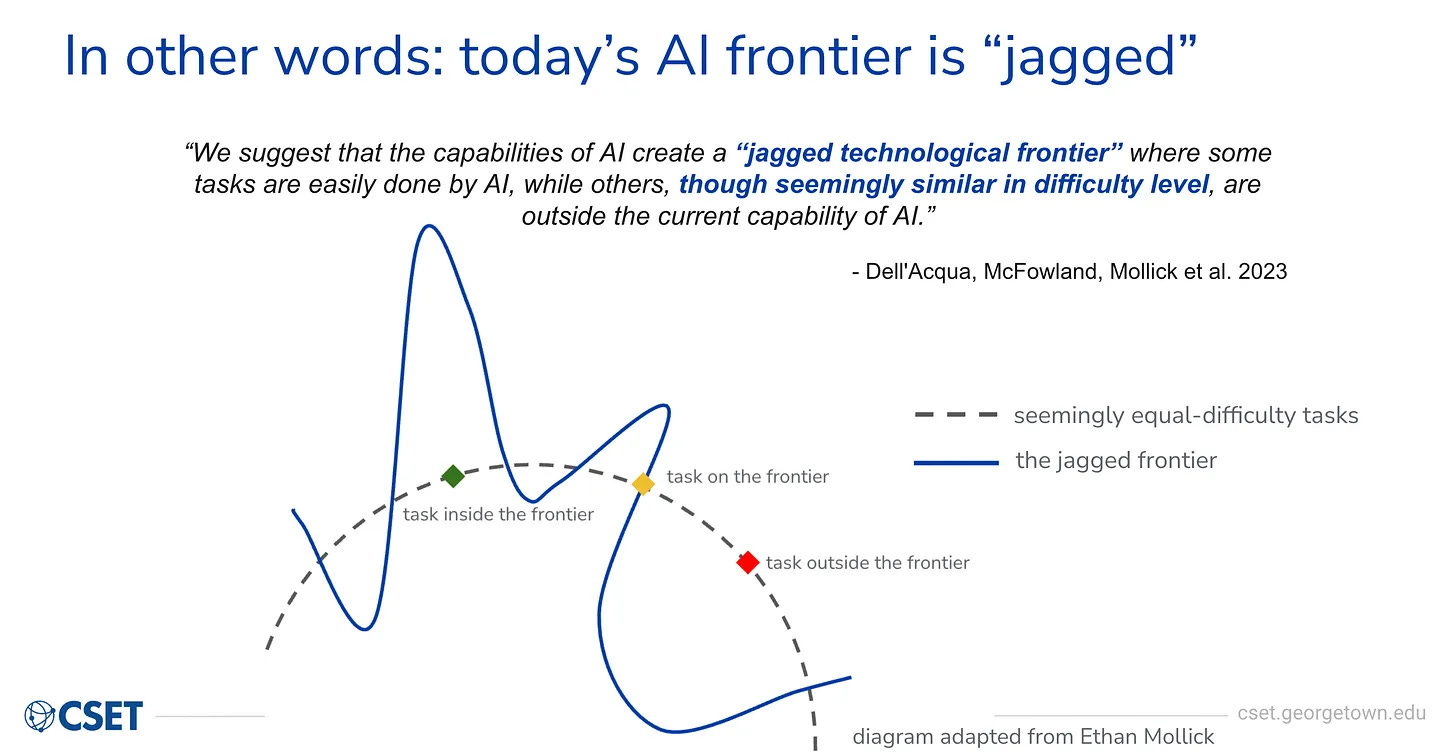

Additionally, these capabilities will likely remain ‘jagged’.

Jaggedness is a concept that explains how current AI models are good performing some tasks yet are remain surprisingly poor at performing other tasks. This inconsistency is what prevents models from achieving what one might observe as a general intelligence. It reveals AI’s uneven capability frontier.

Helen Toner has a very good talk (with a written version on Substack) which explains this concept. In that talk, Toner explains why this jaggedness seems to occur:

Task verifiability. Models really excel at tasks that are easy to verify like coding; to check that the model produced the right code, you can simply the run code and check if the code works as instructed. But for other kinds of tasks, it can be more difficult to come up with ways to evaluate models. Toner takes the example of business strategy - how do we evaluate whether a business strategy generated by a model is good or not? Jason Wei, a researcher at Meta Superintelligence Labs, calls this verifier’s law (or the asymmetry of verification) - the ability to train AI to solve a task is proportional to how easily verifiable that task is.

Context window limitations. There is a question of how easy it is to condense the nuance and intricacies of a task into a form that can be included in the context window of an AI model. Code can be included since it is text data that models can easily parse through. But other tasks are much more difficult to copy-and-paste into the context window.

Adversarial environments. Models continue to be brittle. They are generally getting harder to jailbreak but this is still not impossible and can be done in some weird ways (e.g., using poetry).

Cognitive vs physcial domains. AI has so far proven very good at purely cognitive tasks, namely tasks that can be done remotely and digitally. But Toner notes how “there are huge differences between industries, tasks, roles that are very cognitive versus those that are physical.” She uses the example of event planning; some of this can be done remotely, though with certain aspects of the task such as visiting the actual event space or building relationship with vendors, it is “going to be difficult to do [this] if you’re just an AI model just interacting via computer interface.”

So AI progress may slow down and continue to be jagged unless a new advancement is made that enables models to take the next leap.

The reckoning after the bubble pops

AI hype is fuelling a financial bubble that at some point will pop, and this could happen next year.

Last week, I wrote about what happens when the AI bubble pops. In that newsletter, I predict that we will get more ads because the frontier developers will need to turn to a reliable revenue stream to justify the huge amount of investments going into AI. Surveillance capitalism is a proven model that these companies are likely to rely on in the end.

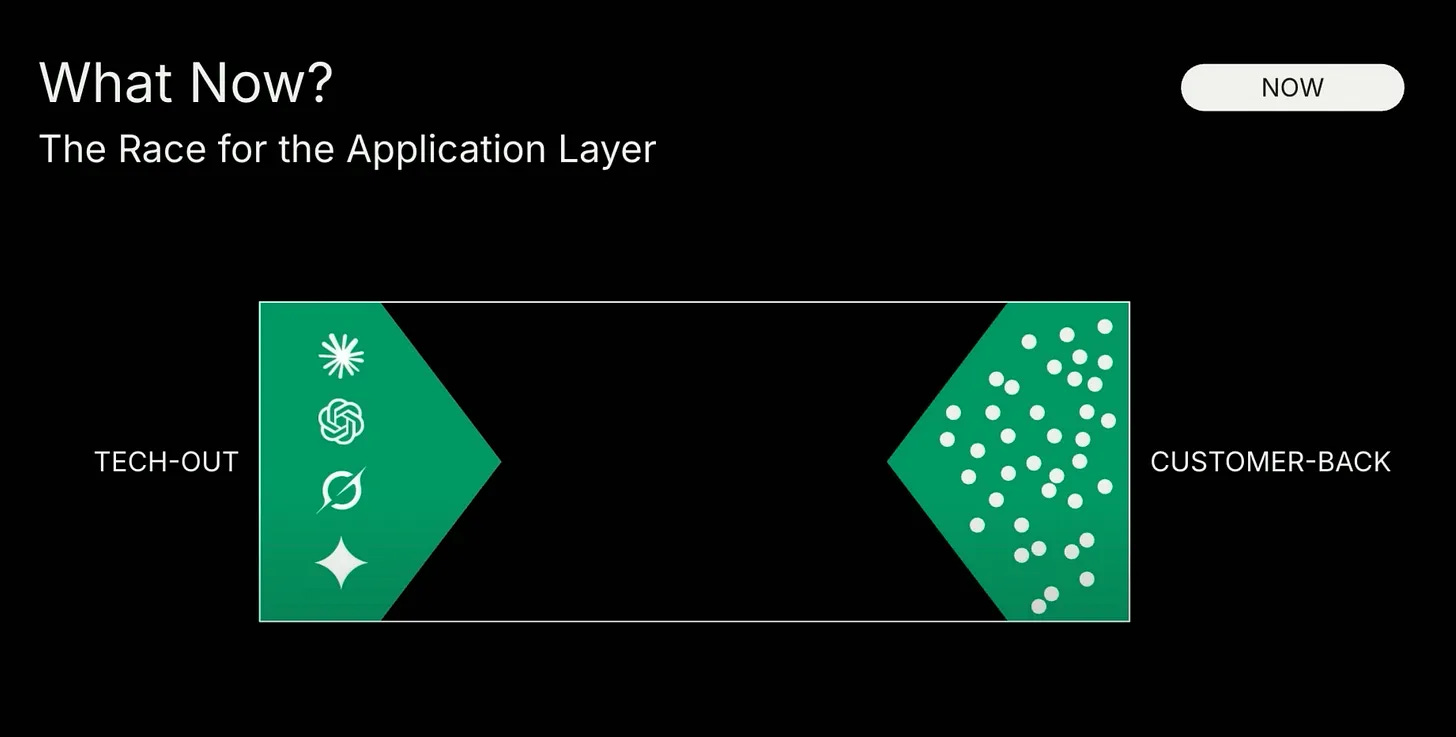

But apart from the frontier developers that manage to find a reliable revenue stream (whether its ads or something else), which other companies in application layer will survive?

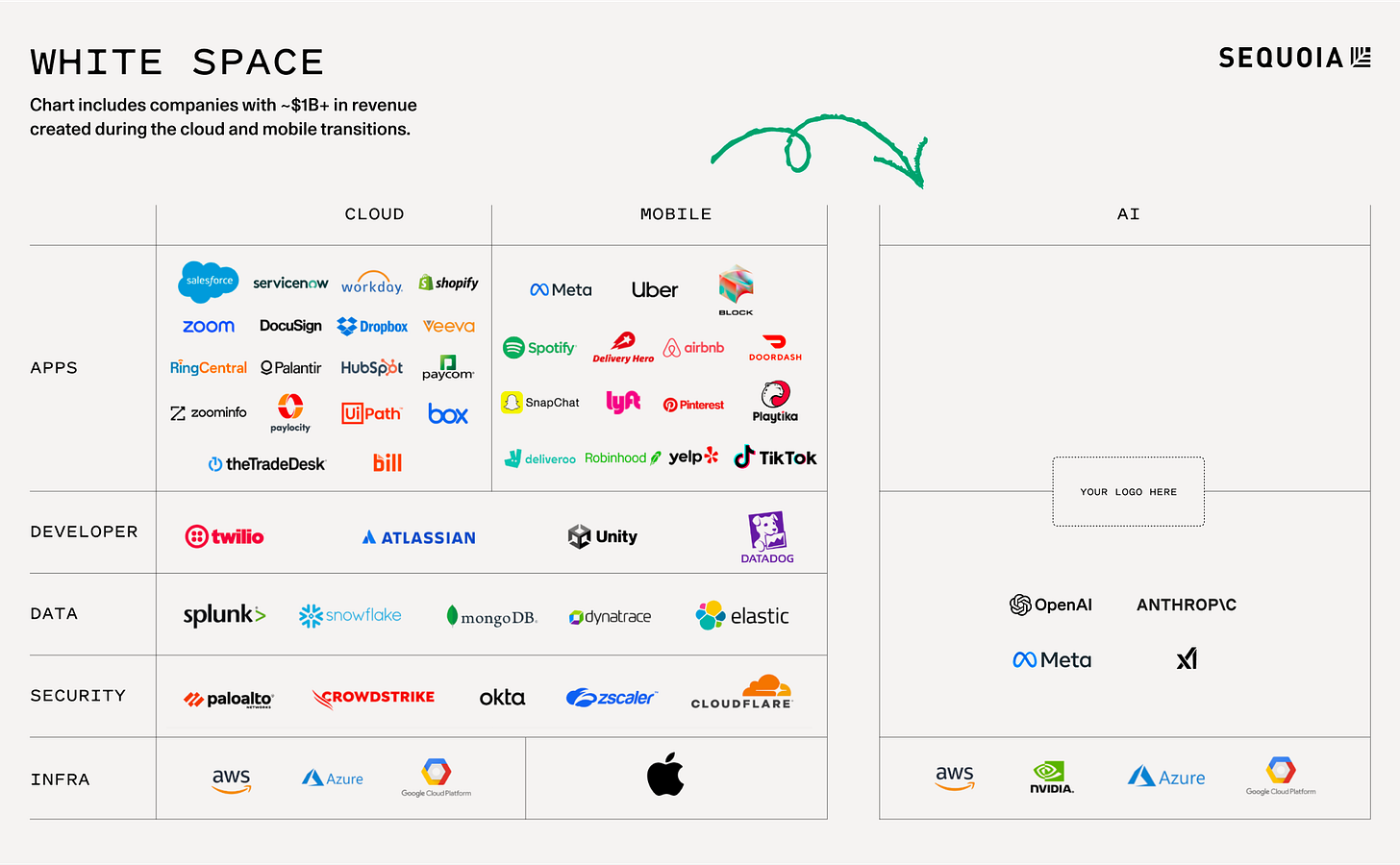

On one view, you could say that basically none of them survive in the end. Why? While the AI stack is highly distributed in terms of control and power, the player at the top of it all is Nvidia.

AI startups are highly reliant on the foundation model developers. The foundation model developers are highly reliant on the cloud service providers. The cloud service providers are highly reliant on the GPU designers, of which Nvidia is (currently) the best. Silicon is the thing that keeps the AI industry going.

From this perspective, the ‘LLM wrappers’ (those building applications on top of foundation models) seem to be the most vulnerable in the value chain. They are so highly dependent on those higher up in the chain, especially the model providers, that it is difficult to see how they become self-sustainable. Without the general-purpose AI models to build on top of, which form the literal foundation of the product, the wrappers would be hollow - the various features, workflows and integrations would not have the cognitive engine to wrap around.

Additionally, model provider themselves have been making their own moves into the application layer. Anthropic’s Claude Code, OpenAI’s Codex and Gemini’s Antigravity are agentic coding products that compete with Cursor, for example.

When the bubble pops, I think many of these wrappers are will disappear. But not all of them.

There will be some that will manage to survive due to being good products. The question is what makes a good AI product?

So far, you could say that three particular use cases have seemed the most promising.

The first are the standard chatbots. This was the type of deployment that many first became familiar with when introduced to generative AI, and it is a interface that remains quite popular today. OpenAI today boasts over 800 million users of ChatGPT, the user-interface of which has largely remained the same since it launched in November 2022.

What is useful about chatbots is that they are user-friendly. To interact with the underlying model, you simply need to enter a natural language prompt into the textbox and the chatbot will output a response. It is quite intuitive and straightforward. Over time, different providers have added various components and features to these types of products, like web search and the ability to attach files. The basic mode of interaction, however, has remained the same.

Another promising use case is auto-completion, particularly with coding. With this type of product, direct interaction with the model is not even required; you simply start typing your code in the editor, and the app will start suggesting what the rest of that code should look like. The model becomes more neatly integrated with the users’ workflow, in a way that is at least as intuitive as talking to a chatbot.

Lastly, another slowly growing use case is the AI agent. It is a further step up from traditional chatbots and even auto-completion. This is because AI agents are designed to go beyond simple single-turn, input-then-output interactions; they can identify the steps required to complete a task, access the right tools and data, and use feedback loops to verify that it has completed the task set. And it does this all with very little human control.

If done correctly, companies building AI agents will not just be building new products, as a16z suggests:

The implication is profound. AI is moving from a static chat interface to an active participant in work. The competitive frontier is no longer only about accuracy or benchmarks. It is about orchestration, control, and a model’s ability to operate as a reliable agent. For founders, this represents a strategic opening. Products that embrace these workflows early will define the next generation of AI-native applications.

There will therefore be a premium for products incorporating “agentic” capabilities, persistent memory, autonomous workflows, and continuous learning, enabled by emerging infrastructure like the model context protocol. This represents a movement toward an “Agentic Web” where autonomous systems coordinate across platforms, fundamentally changing business processes from human-mediated to autonomously optimised operations.

Other use cases may also emerge during this AI hype cycle. But chatbots, auto-completion and agents seem to remain the most promising so far, with many products combining all three.

Overall though, the challenge that those in the application layer will face going forward is fourfold:

Model capabilities slowing down and new research in model development being required to discover the next breakthrough

Model capabilities therefore remaining jagged and subject to some notable weaknesses

The AI bubble popping and easy money from investors going away

Competition from frontier developers increasing as they start to build products for the more promising AI use cases (chatbots, auto-completion and agents)

In essence, those who manage to build good products despite these challenges will survive. And I would argue that the key to building a good AI product is governance.

What will not change for AI in 2026

AI development will remain a highly complex endeavour in 2026, and governance is about creating a system for managing that complexity.

Unfortunately, most AI startups will not care about governance until they think it starts to actually matter. This means that they will only start to think about it when the user complaints start coming, when regulators start knocking on their door or when they get dragged into legal proceedings.

But by the time an AI developer gets to these unfortunate stages, governance becomes painful and bureaucratic in a way that makes it feel like they are walking through treacle. They end up needing to retroactively fix things, making clunky changes to the product and the underlying processes to build it.

The truth is, if you think about governance from the beginning, you do not have to deal with such a mess and you can build a much better product.

In fact, thinking about governance from the beginning is essential.

Looking at the current issues that companies are facing when building with AI models, the top one seems to be the non-deterministic nature of these models; they are programmed implicitly (’hit and hope’) and sometimes things go wrong and the solution is unclear or really tricky. As Toner and Sutskever have noted, these models are jagged and that will likely remain the case until research produces something new that fixes it.

New models, however, are not the only way to get petter performance. You can also get better performance from current models that are governed properly.

If developers do not take governance seriously from the beginning, then those will be the developers that end up building AI applications that are just not very good, and either disappoint users at best or harm them at worse.

This is because governance is not just about legal compliance. Governance is about implementing technical, organisational and legal measures to manage the benefits and risks of AI systems.

Accordingly, good governance delivers on the core aspects of AI engineering: meticulous attention to data quality, feedback loops, user interaction and measurement discipline. This is what generates AI products that actually work, build trust and deliver value.

Using Chip Huyen’s framework, I dive deeper into the things that make a good AI product and how these things are closely related to governance work:

Talking to users

Building reliable platforms

Managing data

Optimising for end-to-end workflows

Writing better prompts

Talking to users

How do you know if your product is any good if you do not get feedback from the people who use it?

Building AI products, as with any other kind of product, consists of a hypothesis that needs to be tested. That hypothesis is tested by gathering feedback.

The nature of this feedback will depend on the product being built. But generally, this feedback ought to touch on how users interact with the product, the features they use, what they like and do not like and where they drop off.

The more feedback gathered the better. Building openly and engaging with users generates feedback that in turn reveals the path of progress for the product.

This is exactly the approach that Harvey took.

Harvey provides AI legal software for some of the biggest law firms in the world, including CMS, Dentons and Reed Smith.

And this should be regarded as a great feat, because law firms are some of the most traditional, conservative and (arguably) outdated organisations you could ever come across. They are full of risk-averse legal professionals most of whom are highly sceptical of AI.

So how did Harvey manage to acquire these firms as customers for its product?

What Harvey did not do is take the approach of just building a product and then trying to bulldoze its way through the legal industry with little care for its needs and interests.

Instead, Harvey looked to ‘partner with the vertical’. This means that it took time to engage with law firms and understand the problems they are facing and therefore what their use cases for AI might look like. By partnering with larger firms in particular, Harvey was able to get a broad sense of the use cases pervasive across the industry and what would be most important for an AI product for legal.

Harvey figured out that, for its product to actually work for lawyers, they needed to make lawyers essentially co-designers of the product.

One of the key aspects of governance is ensuring that the AI product being developed meets the necessary requirements. Those requirements are not just about what is mandated by legal frameworks - they also include the specific functions that the product should execute. Getting feedback from users means that you are more likely come up with requirements that meet user needs and therefore build the trustworthy and valuable products that they want.

Reliable platforms

A good AI product is one in which it is easy for teams to change aspects of the system as well as test how those changes behave in the real-world environment.

In other words, the AI product needs a good platform.

What is meant by platform here is the infrastructure and tooling that makes the underlying system for the product. This includes elements for prompt orchestration, retrieval, evaluation, logging, monitoring and other important elements.

For all this to be “reliable”, developers will need to think about this from an operational and product perspective:

Operational (i.e., backend) reliability involves stable latency, low error rates, resilience to model provider outages or changes, and good observability (achieved with logs, metrics and traces).

Product (i.e., frontend) reliability is about the system behaving predictably enough that you can measure quality, compare variants, and ship changes without constantly breaking the user experience.

This is important because AI models are probabilistic in nature and therefore do not have the predicability of deterministic systems. Instead, they come with a lot of brittleness and instability that has to be managed carefully.

If your platform does not absorb that variability with appropriate safeguards, every experiment feels risky and slow, which kills the speed of iteration.

Furthermore, a reliable platform is one that is easy to iterate and test. Being able to talk to users is one thing. But if you cannot also enact the changes they suggest, or have the product conform to the requirements established based on user needs, then the product will likely fail to deliver a decent user experience. It is hard to build trust and deliver value from there.

From a governance perspective, reliable platforms are critical for the validity, reliability and robustness of the product:

Validity means being able to use objective evidence to confirm that the requirements for the system have been fulfilled.

Reliability means that the system performs as required without failure over its entire lifecycle.

Robustness means that the system is able to maintain its level of performance under different circumstances.

Additionally, focusing on building more reliable platforms rather than using the latest models or agentic frameworks reduces risk. This is because it prevents developers from unnecessarily drowning themselves in the risks of integrating the latest shiny object forces them to deal with the problems at hand. The threat vector stays smaller and more controllable when focusing on making the whole system work well rather than just the individual parts.

Data management

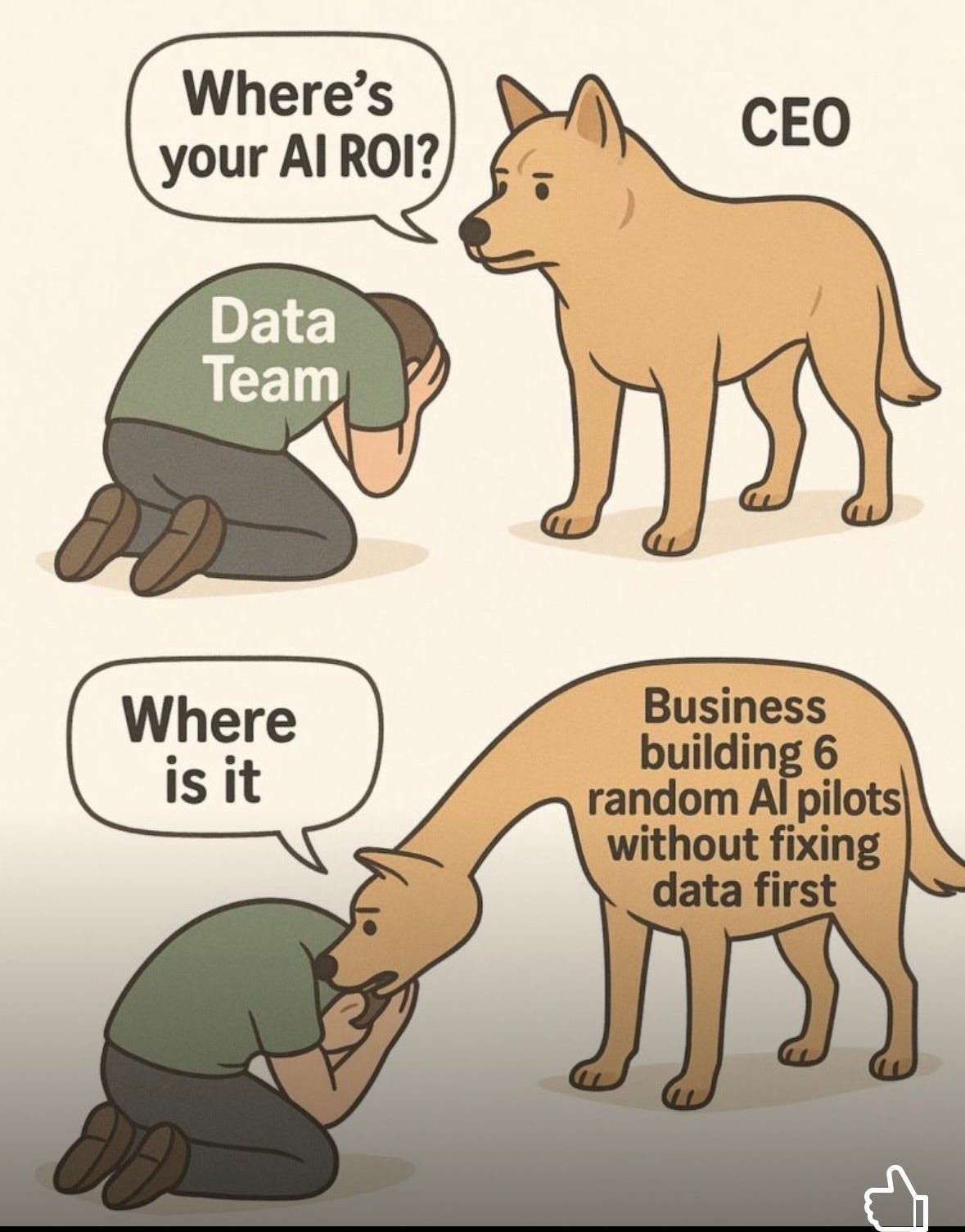

The classic saying of ‘garbage in, garbage out’ still remains extremely relevant for building AI products.

But this is not just about collecting and using good data.

Data management is also about having measures in place to ensure good data quality processes. Good data can become bad data if it is not handled correctly.

This means that developers will need to think about the following:

Identifying the data needed to fuel the system, where it can be sourced from publicly available datasets, web-scraped datasets, licensed datasets or proprietary datasets

Acquiring the data from the relevant sources

Preparing the collected data for building the system

Managing the data throughout its lifecycle, including its decommissioning when it is no longer needed

For Huyen, the biggest gains here come from “data preparation, such as better chunking algorithms, rewriting data into Q&A format, or adding the right context/summary/metadata to each chunk.”

Data management can be a crucial part of the moat for an AI product. Foundation models may be trained on huge amounts of data, but the probability distribution generated from it will be quite broad and general. By using high-quality datasets that are more domain-specific, AI models can be better leveraged for building features and workflows that satisfy user needs and behaviour.

Furthermore, as Toner has pointed out, a key consideration for AI developers is how easy is it to condense the nuance and intricacies of a task into a form that can be included in the context window for an AI model. From a governance perspective, this might mean coming up with more ways to quantify human activities to feed AI models, and therefore processing more personal data.

If so, then users will need to be reassured that any data collected about them is used in a responsible and ethical manner.

This is another important part of good data management; can you ensure that the use of data complies with relevant data protection requirements? Principles like lawfulness, purpose limitation and data minimisation will play a role here.

Optimising for end-to-end workflows

AI models are just one part of the wider system.

Yes, AI products do ‘wrap’ around the model. But the elements that wrap around it are just as important as the model itself.

If you have a good model, its capabilities are limited if the workflows built with it are not good. Developers should not forget to optimise these workflows and not just rely on the model making up for this shortfall.

This is an important element for Harvey. It treats chat interfaces as a window to the rest of the product; it should be easy to use this interface to get to the other parts of the product. It should be able to route queries to the right workflows, which then retrieve the right information and use the right tools to complete the task accurately.

In essence, the product should be good at workflow routing as well as model routing; each workflow should solve a particular problem, and the product should be good at routing requests to the right workflow. This creates the optimal user experience.

Good workflows are what will separate the wrappers from the model providers. It enables the different features, integrations and other elements of the product to shine in a way that the frontier developers cannot easily replicate. It is therefore important to think about the complexity of the work that the product will be used for and how the product will tackle that.

Better workflows also help to mitigate risk. It reduces the chances of the agent doing something wrong, or accessing data that it should not, or trapping itself in loops that require human intervention.

Writing better prompts

Foundation models are general-purpose, and by default they provide general answers to prompts.

If you want models to perform a specific task in a specific way in a specific domain, then the instructions given to it also need to be specific and detailed enough.

This is still important for agents despite the fact that they operate with more autonomy. System prompts are critical for giving the agent the correct starting point and setting it on the right path to accurately and reliably complete a given task. Tool prompts are important for instructing on which tools the agent should use and when. And protocols provide further guidance on the workflow that should be followed by the agent.

All three require good prompt writing.

And this is not necessarily a technical skill. It is an important skill to have in general that can be leveraged for AI development and use.

Governance is the long game

Ultimately, implementing good governance for good products requires long-term thinking.

Long-term thinking is needed to do hard things. It is conducive for the incentives, processes and people required to see out projects that take time to execute.

And doing hard things is an effective way of gaining a competitive advantage.

Most organisations will not do hard things like governance at first. There is therefore a great advantage to be gained from doing what others are unwilling to do.

Governance is hard because it is not a one-time box-tick.

It is a process.

It is about acknowledging that building good products requires deep focus on building solutions for real user problems, careful iteration and proactive management.

But by taking governance head on, and early on, it presents another means for longevity and outlasting the competition. When governance is built-in, and not just an add-on, it puts you ahead of others that start thinking about it too late.

Get governance right and you can be a leader in AI for 2026 and beyond.

But this is just my take on all this. Let me know what you all think.

See you next year.