Purpose limitation and AI development

How this important data protection principle might influence AI engineering projects

TL;DR

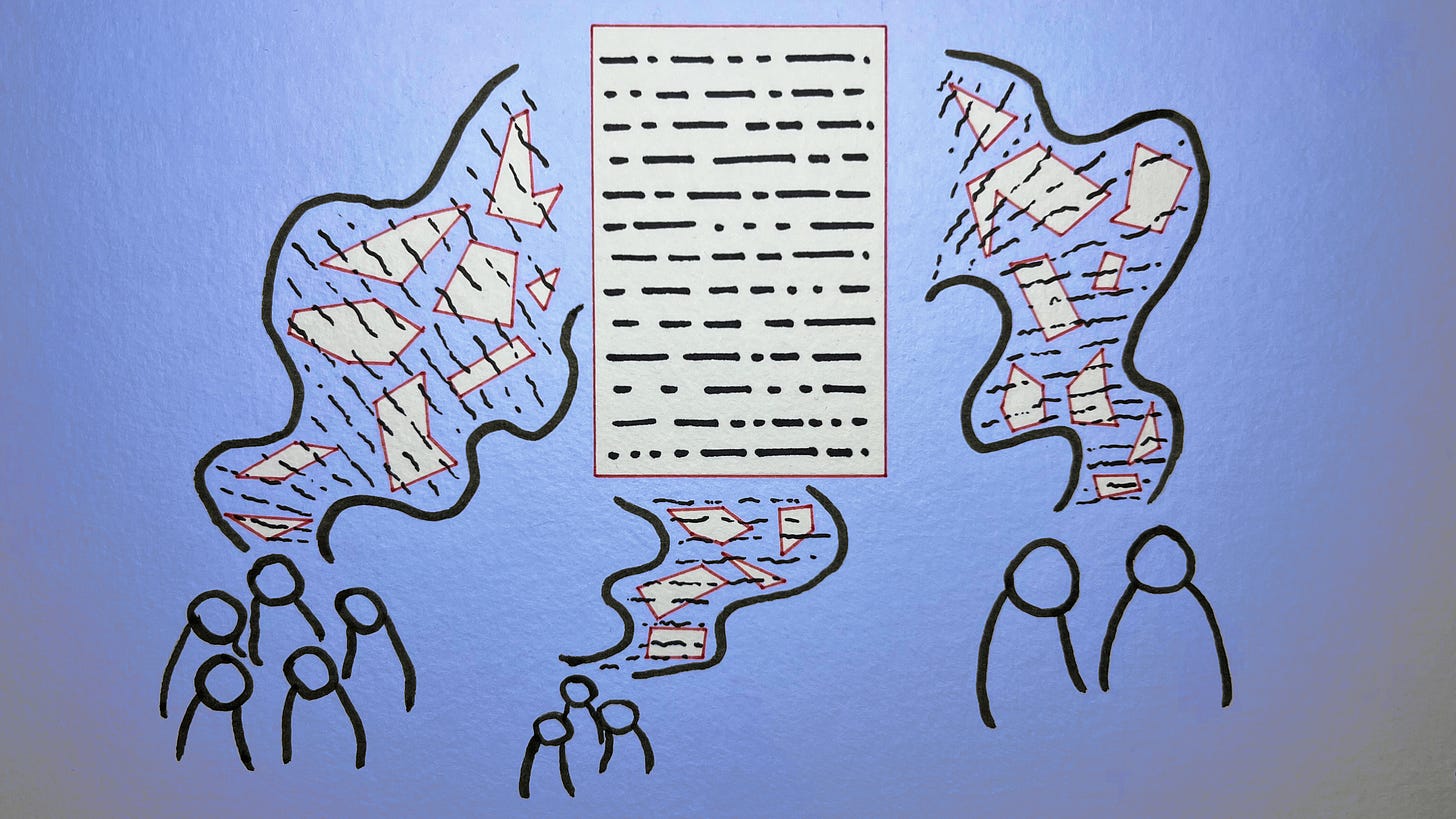

This newsletter is about applying the purpose limitation principle to AI development. It looks at the relevant legal provisions in the GDPR on this principle, its interpretation by courts and regulators, and this legal requirement might influence AI engineering projects.

Here are the key takeaways:

Under the purpose limitation principle, personal data can only be processed for specific purposes that are determined before the data are collected. If the purposes can be fulfilled without processing personal data, then that data should not be used to fulfil those purposes.

If a controller wants to use data collected for one purpose for another purpose (i.e., further processing), this is subject to specific rules under the GDPR. The further processing of data is only permitted in certain circumstances, including where the further processing is compatible with the original purpose, where it is permitted by law or where the data subject has given consent.

The Court of Justice of the European Union and the European Data Protection Board have provided further interpretations and guidance on this principle and how it might apply in practice. This includes some guidance on how purpose limitation may influence AI development.

If the compatibility test for further processing cannot be met, then controllers can only use customer data for model training after obtaining consent from the data subjects. This could be quite difficult depending on the context of the processing, including the relationship the controller has with data subjects.

This means that it is important for controllers ask the fundamental first order questions before commencing an AI project. Without doing this, companies may fall for the AI hype and FOMO, resulting in the implementation of AI systems that are neither very good nor compliant.

A (fictional) scenario

I have written in previous posts about companies using proprietary data to build AI systems. This includes the impact that data-hungry generative AI has on data protection.

In this post, I attempt to take a closer look at the complexities of applying the purpose limitation principle to AI development. I do so using the following fictional scenario:

A car insurance company, CarCare, wants to develop a customer-facing chatbot for its website. The intention is to build a chatbot that its customers can use for quick and easy support access. This includes accessing documents, placing online claims or making payment enquiries.

The company plans to develop this product by fine-tuning a multi-modal large language model (LLM). The trained model will then be deployed with a graphical user interface (GUI) on its website. Training data will consist of 10,000 retained customer support records. This is to ensure that the chatbot exhibits the desired behaviour when responding to customer queries.

The customer support records consist of:

Date and time of contact

Communication channel (phone, email, chat, in-person)

Name of agent or representative involved

Summary or transcript of conversation

Customer inquiries or complaints

Actions taken during the interaction

Resolutions or follow-up steps

Supporting documents or attachments (e.g., scanned IDs, claim forms and photos)

CarCare plans to use supervised fine-tuning, for which the developers will reconfigure the formatting of the records into a set of

(instruction, response)pairs. The model will also be trained with instructions produced by developers to ensure that if it comes across an issue or query that it cannot answer, the customer will be connected with a human operator.

To see how the purpose limitation principle would apply to the above scenario, we would need to consider:

The definition of purpose limitation under the GDPR

The case law on purpose limitation

The regulatory guidance on purpose limitation

The law on purpose limitation

Relevant GDPR provisions

As per Article 5.1(b), under the 'purpose limitation' principle, personal data must be:

...collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes...

Recital (39) states that the data processing purposes "should be explicit and legitimate and determined at the time of the collection of the personal data." It further clarifies that personal data "should be processed only if the purpose of the processing could not reasonably be fulfilled by other means."

Further rules closely related to the purpose limitation principle can be found under Article 6.4. This provision specifies when personal data may be processed for purposes other than the original purpose (i.e., further processing). Such further processing is only permitted where at least one of the following applies:

The further processing purposes are 'compatible' with the original processing purposes

The legal basis for the further processing can be found in either national law or EU law

The data subject gives consent to the further processing of their personal data (which in turn is subject to the specific rules for obtaining consent)

Article 6.4 also sets out the factors that should be taken into account in determining whether the further processing is compatible with the original processing purposes:

Any link between the further processing and the original processing purposes

The context in which the data have been collected and the relationship between the data subject and the controller

The nature of the personal data, particularly whether they are special categories data (as per Article 9)

The possible consequences of the further processing for the data subject

The existence of appropriate safeguards, such as encryption or pseudonymisation

If, taking into account these factors, the compatibility test is satisfied, then a legal basis for the further processing is not required. However, an appropriate legal basis for the original processing purposes is still required.1

Where a controller carries out further processing on the basis of Union or national law or the consent of the data subject, then the compatibility test does not need to be satisfied for the further processing. Even so, the rights of data subjects, where applicable, still apply to that further processing, for example the right to object to processing.2

So overall, under the GDPR's purpose limitation principle:

Personal data can only be processed for specific purposes that are determined before the data are collected.

If the purposes can be fulfilled without processing personal data, then that data should not be used to fulfil those purposes.

The further processing of data is only permitted in certain circumstances, including where the further processing is compatible with the original purpose, where it is permitted by law or where the data subject has given consent.

Ultimately, the controller is responsible for complying with the purpose limitation principle and demonstrating such compliance.3

The Digi case

In the Digi case, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) provided its interpretation on the purpose limitation principle and its application to further processing.

The case concerned Digi, a Hungarian internet provider. Digi had a database called ‘digihu’ which contained the personal data of its customers. The information in digihu related to subscribers of Digi's newsletter as well as data of system administrators who provided access to the interface of the website (www.digi.hu).

Digi had discovered a technical error in its infrastructure which caused problems with its servers. Accordingly, it created a test database, which included copies of personal data stored in digihu, as part of its efforts to resolve the issue. This database contained data on 320,000 data subjects.

Some time later, an ethical hacker contacted Digi to inform the company that he had managed to gain access to the test database. The hacker provided the line of code from the database that contained the vulnerability. Digi fixed the issue and deleted the test database. The company also reported the incident to the Hungarian data protection authority (DPA).

The DPA found that Digi had infringed the purpose limitation and storage limitation principles under the GDPR. This was due to the company failing to delete the test database immediately after carrying out the necessary tests and correcting the fault with its servers. By not deleting the database, a large amount of personal data had been stored in that database for no purpose for nearly 18 months, according to the regulator. Digi was fined around €284,000 for this infringement.

Digi challenged the DPA's findings in a Hungarian court, which then submitted the matter to the CJEU to answer the relevant questions on EU law (or the GDPR to be exact). Those questions included the following:

Should the purpose limitation principle be interpreted in such a way that it allows a controller to store personal data, which has been collected and stored in a lawful and purposeful manner, in another database?

If this parallel storage of personal data is not compatible with the purpose limitation principle, is it compatible with the storage limitation principle for the controller to store in parallel in another database personal data that has otherwise been collected and stored in a lawful and purposeful manner?

In sum, the verdict of the CJEU was that data collected for one purpose could be used for the separate purpose of testing and error correction if the compatibility test under Article 6.4 GDPR can be met.

In coming to this verdict, the Court provided several stipulations regarding the purpose limitation principle:

The principle has two components. The first is that the processing purposes are specified, explicit and legitimate. The second is that data are not processed with purposes incompatible with the original processing purposes.4

The issue of compatible further processing is relevant where the further processing is not identical to the original processing purposes.5

The purpose of the criteria to be considered for the compatibility test is to identify a specific, logical and sufficiently close link between the further processing and the original purposes. This ensures that the further processing does not deviate from the legitimate expectations of the data subject.6 The criteria are also to ensure a balance between predictability and legal certainty on the one hand, and the degree of flexibility for the controller to manage data on the other.7

Although it was ultimately for the Hungarian court to determine the legality of Digi's actions, the CJEU gave its view on the facts of the case:

The original purpose of storing personal data in digihu was the conclusion and performance by Digi of subscription contracts with its customers.8 The test database was created by Digi in order to be able to carry out tests and correct errors regarding its customers.9

There was a specific link between "the conducting of tests and the correction of errors affecting the subscriber database and the performance of the subscription contracts of private customers."10 This is because the errors "may be prejudicial to the provision of the contractually agreed service."11

The further processing (i.e., the testing and correction) did "not deviate from the legitimate expectations of those customers."12 Also, no sensitive data was involved and the subscribers did not face any detrimental consequences from the further processing.13

EDPB guidance

Data protection by design and default

Article 25 requires controllers to ensure that their processing operations adhere to data protection by design and by default (DPbD). This means having "data protection designed into the processing of personal data and as a default setting and this applies throughout the processing lifecycle."14

In its guidelines covering this obligation, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) addresses the purpose limitation principle, which is integral to DPbD. The Board states that the processing operations of the controller should be "shaped by what is necessary to achieve the [processing] purposes."15 This may entail implementing some of the following measures:16

The controller should not connect datasets or perform incompatible further processing

Hashing or encryption should be applied to limit the possibility of repurposing data, accompanied by appropriate policies and contractual obligations on employees and third parties processing personal data

The controller should regularly review whether the processing is necessary for the purposes for which the data was collected and test the design against purpose limitation

Personal data and AI models

Further guidance can be found from the EDPB's opinion on the development and deployment of AI models.

In that opinion, the Board defines AI development as the stages prior to AI model deployment, which includes "code development, collection of training personal data, pre-processing of training personal data, and training."17 When it comes to the data sources used for building the training dataset, controllers should take steps to avoid or limit the collection of personal data where this is possible.18 This may entail using:

Appropriate selection criteria for the training data

Relevant and adequate data sources considering the intended purpose of the data collection

Excluding inappropriate data sources

The EDPB's AI model opinion does not directly address the issue of compatibility of further processing.19 However, the EPDB does mention how the purpose limitation principle should be considered for AI model development and deployment. In particular, the controller should consider the following factors to ensure that the use of any personal data across the AI model lifecycle complies with purpose limitation:20

The type of model the controller plans to develop

The expected functionalities of the model

Whether the model is being developed for internal deployment

Whether the model will be sold or distributed to third parties after development

Whether the model will be deployed for research or commercial purposes

Applying purpose limitation to the CarCare scenario

Given that CarCare is the data controller of the customer support records, it must comply with the purpose limitation principle and demonstrate this compliance. To do this, it needs to identify the original purpose of processing these records and the further processing of these records that it is considering.